Exhibition closed.

Enquiries: hello@the1897.com

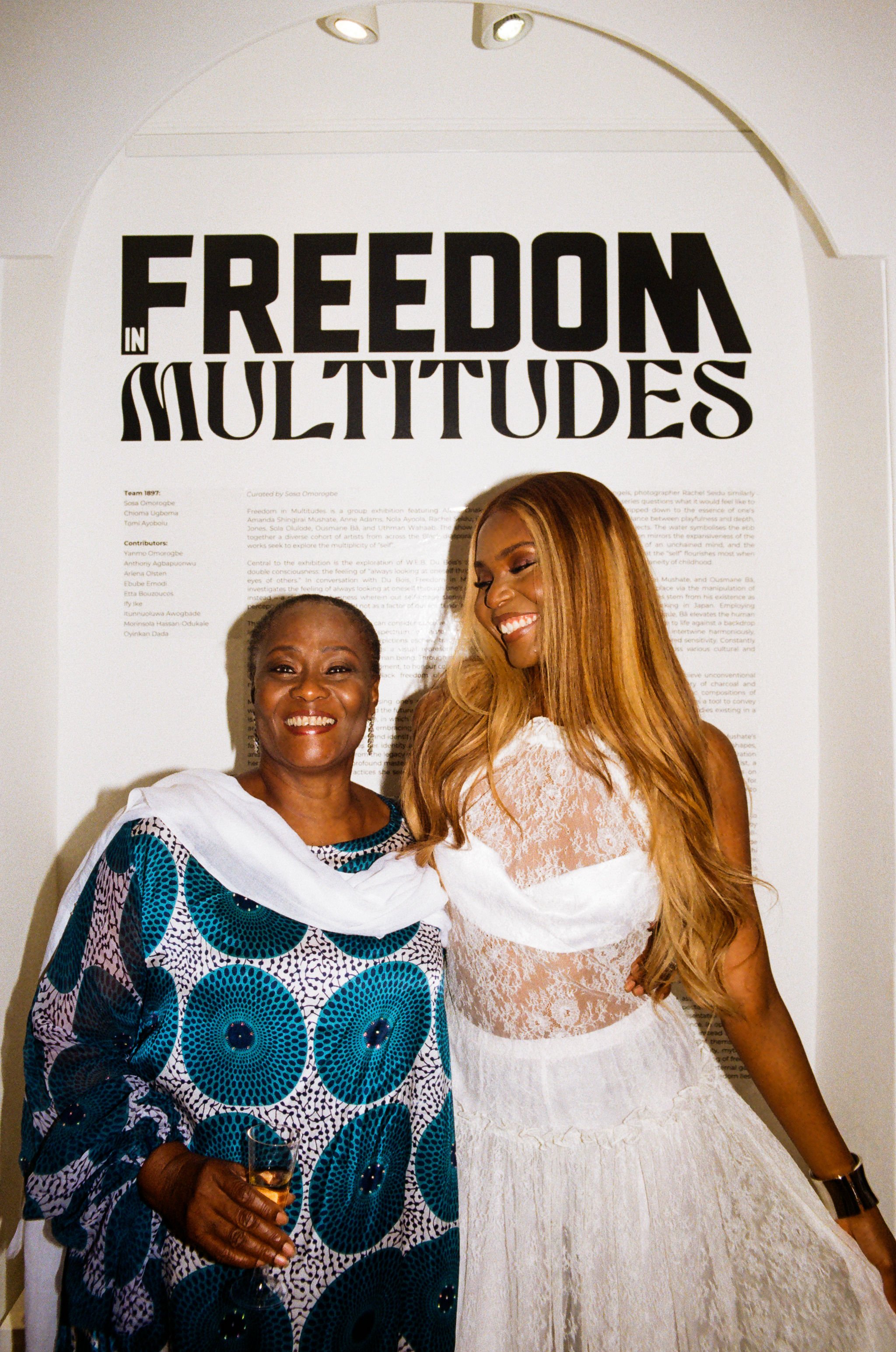

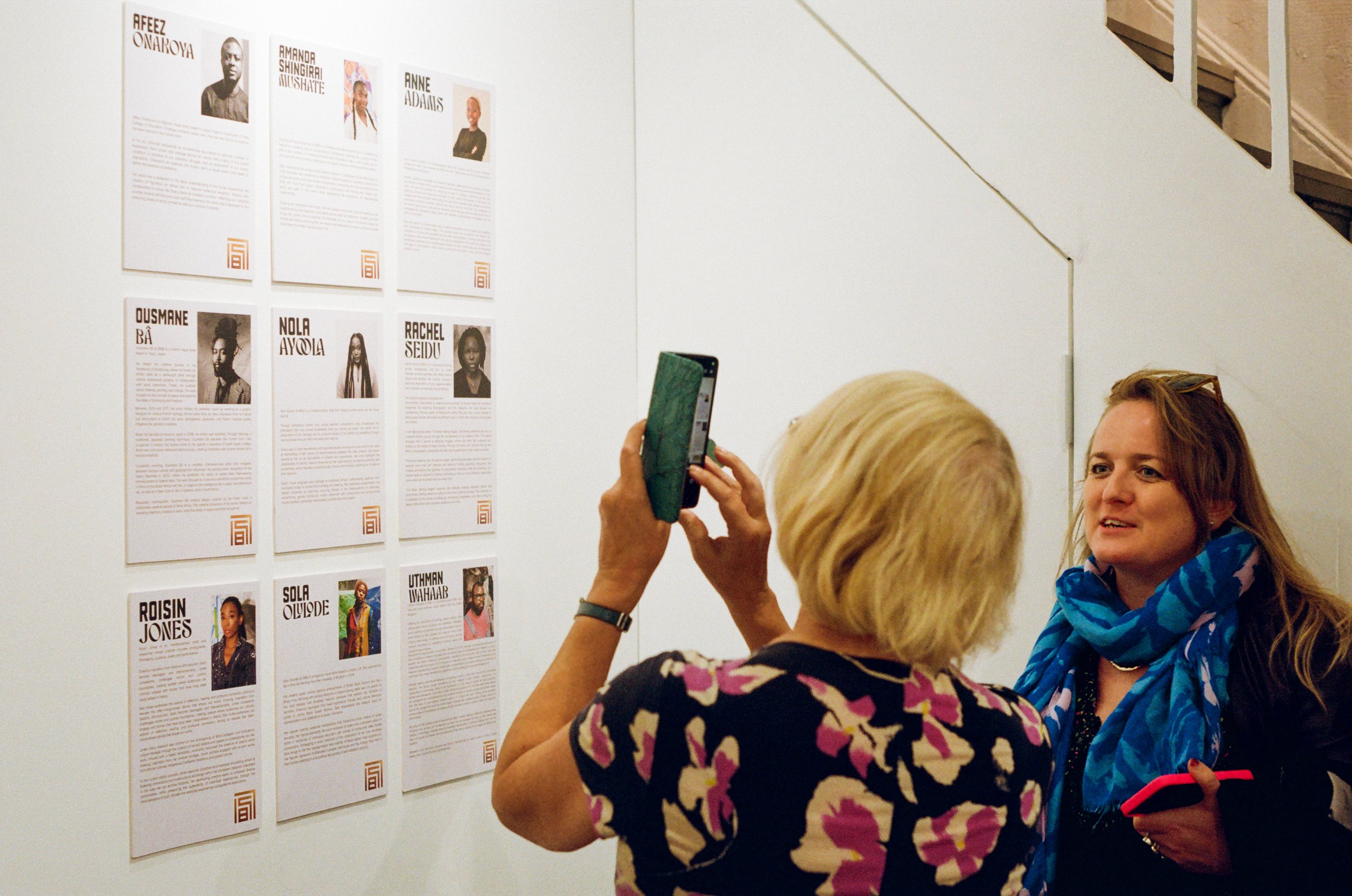

Curated by Sosa Omorogbe, Freedom in Multitudes is a group exhibition featuring Afeez Onakoya, Amanda Shingirai Mushate, Anne Adams, Nola Ayoola, Rachel Seidu, Roisin Jones, Sola Olulode, Ousmane Bâ, and Uthman Wahaab. The show took place from 5-14 October at 32 Connaught Street, London.

Freedom in Multitudes brings together a diverse cohort of artists from across the Black diaspora whose works seek to explore the multiplicity of "self.”

Central to the exhibition is the exploration of W.E.B. Du Bois’s theory of double consciousness: the feeling of “always looking at oneself through the eyes of others.” In conversation with Du Bois, Freedom in Multitudes investigates the feeling of always looking at oneself through one’s own eyes instead—a single consciousness wherein our self-image stems from our perception of what lies within and not as a factor of our existence as "other.

Press

Exhibiting Artists

In The Bubble of Sola’s Love

The Opening Reception of Freedom in Multitudes featured a participatory installation, using light to bathe guests in the warm yellow tones of Sola Olulode’s bubble works on display. The final product of this installation was these photographic bubbles by rosh.png!

Sola Olulode’s works focus on the fluidities of identity among British Black Womxn and Non-Binary individuals, queer intimacies in a utopian context. Her vibrant, textured canvases explore the stages of a relationship between two queer women, reflecting Olulode’s own lived experiences. Olulode’s subjects embody joy, intimacy, and freedom, challenging reductive notions of queer identity.

Opening Reception

Curatorial Statement

Curated by Sosa Omorogbe, Freedom in Multitudes is a group exhibition featuring Afeez Onakoya, Amanda Shingirai Mushate, Anne Adams, Nola Ayoola, Rachel Seidu, Roisin Jones, Sola Olulode, Ousmane Bâ, and Uthman Wahaab. The show will run from 5-14 October at 32 Connaught Street, London.

Freedom in Multitudes brings together a diverse cohort of artists from across the Black diaspora whose works seek to explore the multiplicity of “self”.

Central to the exhibition is the exploration of W.E.B. Du Bois’s theory of double consciousness: the feeling of “always looking at oneself through the eyes of others.” In conversation with Du Bois, Freedom in Multitudes investigates the feeling of always looking at oneself through one’s own eyes instead – a single consciousness wherein our self-image stems from our perception of what lies within and not as a factor of our existence as “other”.

Through the lens of our own eyes, we are able to consider ourselves on a granular level; freely traversing a dynamic spectrum of histories, emotions, experiences, and futures. The artists’ depictions eschew traditionally rigid figuration, recognising its limitations as a visual representation of the complex amalgam that constitutes a human being. Through diverse media, these artists aim to unify rather than fragment, to honour complexity rather than simplify, and to espouse the Black freedom of existing across multitudes.

Multitudes are often understood by using one’s past as a lens through which the present can be examined and the future forecast. This exploration is at the crux of Anne Adams’s practice, in which she interrogates hybridity and nuance in identity formation, embracing plurality and rejecting monolithic narratives of truth, reason, and identity. Exhibiting collage works for the first time, Adams navigates her identity as a sum of past, present, and future. Drawing inspiration from the legacy of pre-colonial Nigerian art, her work is a celebration of the profound mastery and intellectual ingenuity of her predecessors – whose practices she sees as integral to interpreting her own.

Lineage and heritage also play a key role in Nola Ayoola’s work, which pays homage to traditional African craftsmanship practices that have become uncommon in contemporary fine art – from hand-dyed indigo to carved block printing and weaving. Guided by the principle that ‘one cannot understand what one cannot pull apart’, Ayoola’s works document the human experience using organza and cotton to form multidimensional, layered pieces that depict the threads of one’s life woven into a unified whole. Nola’s work is both theoretically and physically layered, telling stories of the interconnections between the past, present, and future, revealing her art as reticulations of dreams and experiences.

Roisin Jones’ Freedom explores the veil between mythology and reality prevalent in the African and Caribbean diasporas. Jones depicts a dream in which she wrestles with an alligator, attempting to subdue it with bonds. Eventually, Jones gives in, allowing the bonds to break and leaving her destiny to fate. This symbolises freedom for both parties: for one, freedom from fear; for the other, freedom from its crippling entrapment. Jones and the alligator then flee the river, with Jones riding on its back, signifying the unification of the artist’s two selves. Not long after she illustrated this dream, Jones decided to pursue art professionally: “It is a reminder to me that the journey to authenticity and self-expression is fraught with danger, but to leap and go with it anyway. It reminds me to answer the call to my vocation as an artist and to embrace oneself in the face of adversity, to be wild and boundless.”

Jones’ depiction of her ultimate destiny as a form of spirit animal references the Jamaican River Mumma, a mythical human-fish/serpent chimera that is believed to be the guardian of the water and its treasures. In her oeuvre, the artist repeatedly draws inspiration from folklore, Afrofuturism, and Black feminist ideologies. Her use of indigenous knowledge and cosmologies as an allegorical framework enables us to understand who we are. Water and River Mumma share the characteristics of being simultaneously nurturing and life-giving, and dangerous and destructive — a reminder of the facets existing within humans.

In her series, I’ve Been Seeing Angels, photographer Rachel Seidu similarly uses nature as a narrative tool. The series questions what it would feel like to free one’s creative mind and be stripped down to the essence of one’s being. It also speaks to the delicate balance between playfulness and depth, using everyday features as totemic objects. The water symbolises the ebb and flow of life, whilst the endless horizon mirrors the expansiveness of the mind; the balloons represent the levity of an unchained mind, and the football adds playfulness, reminding us that the “self” flourishes most when it reconnects with the innocence and spontaneity of childhood.

For artists Afeez Onakoya, Amanda Shingirai Mushate, and Ousmane Bâ, traversing the scope of one’s identity takes place via the manipulation of traditional figuration. Bâ’s works and influences stem from his existence as a Fulani Senegalese-Guinean living and working in Japan. Employing Nihonga, a traditional Japanese painting technique, Bâ elevates the human form. Like sculptures in motion, the bodies come to life against a backdrop of washi paper collage. Warm and cold tones intertwine harmoniously, creating characters with diverse stories but a shared sensitivity. Constantly evolving, Bâ’s transversal practice navigates across various cultural and geographical influences.

Like Bâ, Onakoya employs traditional methods to achieve unconventional results. His works act as a testament to his mastery of charcoal and figuration, transcending boundaries to create dynamic compositions of contorted, kinetic bodies. Exploring the efficacy of form as a tool to convey emotions, Onakoya’s works compose a visual poem of bodies existing in a liminal space — a place where they are free to simply be.

This lack of constraint is a defining feature of Amanda Shingirai Mushate’s works, which depict her experiences as an amalgamation of lines, shapes, colours, and threads. Mushate’s evocative pieces on canvas draw inspiration from music and the layers of her identities, most notably as an artist, a mother, and a wife. For Mushate, every feature of the whole takes on different characteristics, and her canvases act as the meeting ground for the multitudes where abstract forms and conflicting colours converge into a harmonious kaleidoscope.

Form plays a distinct role in Uthman Wahaab’s work, as he uses it to critique societal beauty standards imposed on the female form by celebrating the corpulent female body. His works offer a world where full-figured women, unapologetically engaging in everyday activities, exude confidence and freedom. A continuation of his decade-long Where is Chi Chi? series, Wahaab’s women are the picture of bucolic ease and leisure. With each brushstroke, Wahaab champions the freedom of being, and his figures embody self-determined existence liberated from the gaze of external judgement.

Comfort is a defining feature of Sola Olulode’s subjects. The artist explores the fluidities of identity through the lens of British Black women and non-binary individuals, celebrating queer intimacies in a deeply utopian context. Her vibrant, textural canvases embody relationships that transcend reductive notions of queer identity. Olulode’s subjects are free – they dance, laugh, and exude unfiltered joy. The featured works explore the stages of a relationship between two queer women. The subjects entwine their separate viewpoints into one singular, tender consciousness, reflecting Olulode’s own lived experiences. The internal gaze depicted centres the warmth and depth of queer connections, free from societal impositions.

In Freedom in Multitudes, the artists collectively assert their agency to redefine self-perception, moving beyond external expectations and societal limitations. The exhibition challenges monolithic representations of identity by showcasing the depth and richness of Black existence. In opposition to Du Bois’s theory of double consciousness, these artists instead choose to centre themselves wholly, disregarding the placement of themselves as “other”. Through explorations of heritage, materialism, fluidity, mythology, and form, each artist brings forth a multifaceted understanding of freedom—one that is grounded in self-awareness and liberated from external gazes. By centring the internal gaze, the exhibition posits that true freedom lies in embracing the complexities and contradictions of our multitudes.